|

Patrick Donohoe (1806 - 1854)

Young Irelander, "a Felon of Our Land," a

Van Diemen’s Land Exile,

a

Writer and Publisher and, a Penal Colony Escapee.

Under normal

circumstances Patrick Donohoe would have led his life in relative obscurity despite

having participated in the 1848 Young Ireland Rising. What changed that

probability was a meeting with the Rising's

Confederate leadership in Tipperary

where he was sent to

brief them of the situation back in Dublin. That task, together with his presence

at subsequent leadership meetings and his participation in

an attempt to start a Rising in Waterford

with Thomas Francis Meagher, sealed his

fate. As a consequence, he has the dubious honor of being categorized as

one of the seven Young Ireland leaders exiled to Van Diemen's Land and

immortalized as a "Felon of our Land" alongside the luminaries of the

Young Ireland movement.

Growing up a subject of British Imperialism Growing up a subject of British Imperialism

Patrick Donohoe also known as Patrick O'Donoghue

was born in Clonegal, Co. Carlow in 1806. Little is known of his early

life or adolescence, that is to say, who his parents were, what they did

for a living, if he had siblings, or where he received his education.

Some accounts of his early years state that he attended Trinity College

in Dublin and that his father, Michael Donohoe, was a schoolteacher.

Whether or not these accounts are accurate, it’s obvious that he

received a first-class education based on the skills he possessed to

function as a law clerk and later as a writer and newspaper publisher

while in forced exile in Van Diemen's Land, Australia.

In the dawn of the 19th century, at the time of Donohoe's birth, Ireland

was still in a state of trauma resulting from the quelling of the 1798

and 1803 Risings. The systemic brutality of the British army and their

yeomanry cohorts who reveled in inflicting unimaginable cruelty on

captured

croppies

and innocent civilians upon whom they chanced was by any measure eerily

inhumane. As if the awful conditions that caused the captive Irish to

rebel in the first place were not enough to render them permanently

predisposed to servility, the brutality of the overlord’s response to

the Risings, the Act of Union of 1801, and the lingering remnants of the

Penal Laws were all stark reminders that the British considered

bountiful Ireland to be theirs, to do with as they pleased.

Despite the iron fist that hovered over the vanquished Irish people, the

spirit of freedom that inspired

Wolfe Tone,

Napper Tandy,

Robert Emmet, Thomas Russell, Sarah Curran, and the McCracken

brothers and their sister Mary lived on. Their sacrifices and those of

the countless thousands of others who died for Ireland's freedom were

not in vain as they inspired successive generations to rise against the

scourge of imperialism.

By the mid-1840s, Donohoe was living in Dublin with his wife and

daughter and working as a law clerk with W. McGrath in Gardiner Street.

His initial involvement in political activism was as a member of the

Repeal Association which was established in 1830 by Daniel O'Connell to

campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union of 1801 between Great

Britain and Ireland and to restore the Irish parliament.

The Repeal Association and Young Ireland

O'Connell was a Kerry native and a member of the British Parliament who

believed that he could achieve repeal through constitutional means by

supporting the liberal Whig Party which held power in England through

most of the 1830s. That all changed in the General Election of 1841 when

the conservative Tories ousted

the Whigs and Robert Peel became prime minister. Historically, the

Tories were dismissive of the Irish and their Members of Parliament

(MPs) and were not about to restore the Irish parliament or entertain

O'Connell's entreaties.

In 1842, some of the younger members of the Repeal Association launched

The Nation, a nationalist newspaper that initially supported the

Repeal Association and its campaign. The newspaper and its founders

Charles Gavan Duffy,

Thomas Osborne Davis, and

John Blake Dillon were described by

the historian T. F. O’Sullivan as

follows:

“There has never been published in this, or any other country, a

journal, which was imbued with higher ideals of nationality, which

attracted such a brilliant band of writers in prose and verse, which

inspired such widespread enthusiasm, or which exercised a greater

influence over all classes of its readers, which after a time included

every section of the community".

Having declared 1843 to be "The Repeal Year," O'Connell began organizing

monster meetings across the country. At one such meeting on the Hill of

Tara on August 15, 1843, the crowd size was estimated to be close to

three quarters of a million by The Times newspaper. The

next monster meeting which was planned for October 8 in Clontarf was

banned by Dublin Castle, aka the British government's seat of power in

Ireland. Playing by British rules, O'Connell acquiesced to the ban by

calling off the meeting as tens of thousands were on their way to

Clontarf. To further humiliate O'Connell,

apparatchiks in

Dublin Castle charged him with conspiracy and sentenced him to twelve

months in prison. He was released after three months.

That was the beginning of the end of the Repeal Committee. Lacking

direction and effective leadership and brewing dissension within its

ranks, the Repeal Association gradually faded away. The death knell was

dealt by 23-year-old

Thomas Francis Meagher

on July 20, 1846, in Conciliation Hall in Dublin during O'Connell's

"Peace Resolutions" debates wherein he proposed an alliance with the

Whigs and a commitment by Committee members to renounce military force

to combat oppression. After Charles Gavan Duffy dealt with the absurdity

of the proposed Whig pact, Meagher delivered his

"Abhor the Sword"

speech in defense of militarism. After Meagher was interrupted by

O'Connell's son John, he left the hall with his "Young Ireland" cohorts.

"Young Ireland" was a term coined by O'Connell to denigrate the young

members of the Repeal Association who disagreed with his policies

that cast Ireland as a

dependent of England who must play by its rules to subsist.

Young, educated, and ambitious, the Young Irelanders were the brains of

the Repeal Association. They believed that Ireland was capable of much

more if free from the shackles of imperialism maintained by military

might, landlordism, sectarianism, and religious dogma. To that end they

labored with the voice of reason, the power of the written word, the

belief in inherent humanity, and the notion that right would trump evil.

At the same time, they understood the prevailing evil that drove the

United Irishmen to rebellion was the same entity the Repeal Association

was trying to reason with.

As

best as can be determined, Donohoe was not a very active member of the

Repeal Association during its existence, other than being a member,

paying his dues, and attending meetings. Some accounts suggest that he

contributed copy to The Nation newspaper using a non de plume as

a self-protection measure. However, after the "Peace Resolutions"

debacle, he left Conciliation Hall with his younger companions, a

fateful act that changed the course of his life, exposing him to the

tentacles of Dublin Castle and barbaric imperial laws.

The Great Hunger and the Irish Confederation

While all that was playing out, the Great Hunger of 1845 - 1852

had taken a foothold in Ireland and was laying waste to the western

areas of the country. By 1846, the potato crop had completely failed

across the entire country, resulting in widespread starvation and the

onset of mass coffinless graves dotting the Irish countryside and coffin

ships plying the Atlantic with human cargoes fleeing the calamity. The

laissez-faire response

of the British government to the unfolding disaster, plus the

ineptitude of the Irish MPs in Westminster, portended a calamity of

unimaginable proportions.

John Mitchel

described the Great Hunger in the following excerpt taken from one of

his many articles on the subject.

"Further, I have called it an artificial famine: that is to say, it was

a famine which desolated a rich and fertile island, that produced every

year abundance and superabundance to sustain all her people and many

more. The English, indeed, call that famine a ‘dispensation of

Providence;’ and ascribe it entirely to the blight of the potatoes. But

potatoes failed in like manner all over Europe; yet there was no famine

save in Ireland. The British account of the matter, then, is first, a

fraud - second, a blasphemy. The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato

blight, but the English created the famine."

On January 13, 1847,

Mitchel, Meagher,

William Smith O’Brien, Gavan Duffy,

and other Young Irelanders, including Donohoe, founded the Irish

Confederation. Donohoe was given a seat on its Executive Council.

Confederate Clubs were set

up in Dublin and in a number of provincial towns to allow the people to

participate and have their voices heard. To further accommodate

their members, the Clubs

held meetings, set up libraries and reading rooms, sponsored lectures,

and disseminated news and information alerting people to the worsening

food shortages and attendant diseases spreading throughout the country.

Initially the aims of the Irish Confederation were no different from

those of the Repeal Association. Their focus was on achieving Repeal

without succumbing to the Anglicization of Ireland or to the patronage

and corruption that beset the Repeal Association. However, by 1848 the

worsening situation in Ireland and the lack of an effective British

response was reinforcing the belief espoused by John Mitchel that

Ireland must break free of England by any means possible to end the

incessant cycle of starvation and disease. Having exhausted all

peaceful means to bring about change, the leaders of the Irish

Confederation concluded that force was the only viable option open to

them, and thenceforth set about planning for an insurrection. Whatever

qualms they may have had were assuaged by news of

revolutions throughout

Europe against absolutist regimes by young intellectuals evoking the

doctrine of natural rights and the "rights of man" rooted in the ideals

of the Enlightenment. The situation in Ireland was catastrophic. The

death toll was climbing exponentially from starvation and diseases. That

was happening at the same time that ships laden with wheat, barley,

oats, and livestock were leaving Irish ports for English to ensure that

the people there were well provisioned to withstand the effects of the

same blight that was devastating Ireland. They reasoned that if such a

situation did not warrant the use of force, what would?

The Young Ireland Rising of 1848; Capture, Trial and Exile

Despite the depiction of the 1848 Rising as a skirmish at a farmhouse

in Co. Tipperary, it was much more than that description would suggest.

What

took place during the abortive Rising in July of 1848 has a history of

its own that bears witness to the desperation and courage of a band of

young Irishmen willing to challenge the might of the British juggernaut

to bring relief to their dying countrymen and women. Although they

failed, they nonetheless left a marker in the annals of modern Irish

history that inspired successive generations to carry on the fight,

always against the overwhelming odds, irrespective of the consequences.

The role Donohoe played during that

tumultuous time is loosely

documented in the accounts of other participants, including Michael

Doheny. In his book The Felon's Track, Doheny explains how

Donohoe became involved in the insurrectionary activities in Co.

Tipperary in July 1848. The following are excerpts from The Felon's

Track.

“He (Donohoe) was much relied on by his friends in the Confederation and

was entrusted with the dispatches to Mr. O’Brien. He proceeded on his

mission to Kilkenny, and there applied to one of the clubs. He was known

to none of the members and became at once the object of suspicion. It

was, accordingly, determined to send him for the rest of the journey,

under arrest, and Stephens and another member were appointed to that

duty. They proceeded in execution of their duty to Cashel, where Mr.

O’Donoghue was warmly welcomed by Mr. O’Brien, whose fate he thenceforth

determined to share. Mr. Stephens came to the same resolution.

With Messrs. Stephens and O’Donoghue, their very desperation acted as

the most ennobling and irresistible inducement. They clung to him to the

last with a fidelity the more untiring in proportion as his

circumstances portended imminent disaster and ruin.”

O’Donoghue was present at the meeting in Ballingarry on the 28th of July

with O’Brien, Dillon, Stephens, James Cantwell, Meagher, Leyne, Devin,

Reilly, John O’Mahony, Doheny, MacManus, John Cavanagh, J.D. Wright, and

D.P. Cunningham.

At that meeting they decided to split up and head to other locations in

hopes of rallying local Confederate members to rise up. Donohoe,

Meagher, and Maurice Leyne headed for the Comeragh mountains in Co.

Waterford where Meagher hoped to make a stand with local Confederate

members. In the meanwhile, contingents of British soldiers and police

were scouring the countryside looking for the Confederate leaders.

Donohoe, Meagher, and Leyne managed to evade capture until August 13

when they were captured near Clonoulty. They were held in Kilmainham

jail until transported to Clonmel in Co. Tipperary in late September to

stand trial on treason-felony charges. Donohoe was tried on October 13

and found guilty by a packed jury. Together with Meagher and

Terence Bellew MacManus, the

death sentence was handed down as follows:

"That sentence is, that you Terence Bellew MacManus, you Patrick

O'Donohoe, and you Thomas Francis Meagher, be taken hence to the place

from whence you came, and be thence drawn on a hurdle to the place of

execution; that each of you be there hanged by the neck until you are

dead, and that afterward the head of each of you shall be severed from

the body, and the body of each divided into four quarters, to be

disposed of as her Majesty may think fit. And may Almighty God have

mercy upon your souls".

To

avoid international condemnation such as occurred after the massacres at

Gibbet Rath

and New Ross in the aftermath of the 1798 Rising, the British government

commuted the death sentences of the Confederate leaders to

transportation to Van Diemen's Land for life. On July 9, 1849, the

Swift set sail for the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land conveying

the "Felons of Our Land" Donohoe, MacManus, Meagher, and

Kevin Izod O'Doherty into exile.

During the voyage Donohoe penned the ruminations of his companions that

were later published in The Nation newspaper. For the ensuing

five years, Donohoe had the unique distinction of being one of the eight

Confederate (Young Ireland) leaders forced into exile for their roles as

leaders of the attempted Rising of 1848. The other seven with whom he

shared that distinction were John Mitchel, William Smith O'Brien, Thomas

Francis Meagher, Terence Bellew MacManus,

John Martin, Kevin Izod O'Doherty,

and William Paul Dowling.

In

1850, the Young Ireland eight were joined by the

Cappoquin seven,

Confederate members who attacked the Cappoquin Police Barracks in

Waterford in September 1849. The attack was organized by

James Fintan Lalor and led by

Joseph Brenan. Brenan, unlike the

others, escaped capture after the attack and managed to make his way to

the United States. The names of the exiled Cappoquin seven are: Richard

Bryan, James Casey, Thomas Donovan, James Lyon, Edward Tobin, Thomas

Wall, and John Walsh.

Donohoe endured more hardship than any of the other exiles due to his

belligerent attitude and defiance of the rules and limitations that came

with his ticket-of-leave (a permit given to a convict to move about and

to get work subject to certain specific conditions). One condition of

his ticket-of-leave was that he had to live and stay within the

boundaries of Hobart in Tasmania. Unable to secure employment as a law

clerk, he started a weekly newspaper titled The Irish Exile

with the help of Irish-born free settlers. The first edition was

published in January of 1850. In short order, Donohoe ran foul on the

governor Sir William Denison who did not appreciate Donohoe's accounts

of the dire economic and political situation in Ireland and the British

government's culpability. He also got in trouble with Denison when he

crossed the restriction

boundary on a clandestine to visit William Smith O'Brien. His

punishment was three months hard labor at

Port Arthur probation

station. After his release he was reassigned to Oatlands in the

interior where supposedly he could not cause any more trouble.

In October of 1850, John Donnellan Balfe arrived in

Van Diemen's Land to the

bewilderment of the exiled Young Irelanders. Balfe, who was a member of

the Irish Confederation, was also a British informer who kept Dublin

Castle abreast of the Confederation's plans for the Rising in 1848.

Needless to say, his presence on the island enraged the Young Irelanders,

none more so than Donohoe. The only way he could extract his revenge

without his newspaper was to out Balfe by telling everyone he met who

Balfe was and how he doomed the Rising and destroyed the lives of so

many brave patriots. In August of 1851, Donohoe was sent back to Port

Arthur to serve another three months of hard labor for having outed

Balfe. Having had enough of Denison's extreme punishment

regimes, he decided to escape when released.

Escape and Freedom

On the way back to Oatlands after completing his sentence, Donohoe gave

the slip to his escorts and made his way

to

Launceston where he hid out with settlers who were Young Ireland

supporters. He lay low for most of 1852 while awaiting his chance to

escape from Van Diemen's Land. In December he was

surreptitiously

placed on board the steamer Yarra Yarra and transported to

Melbourne without detection. From there he travelled to Sydney, Tahiti,

and finally San Francisco, arriving there in June 1853. From San

Francisco he travelled to New York where he received a cool reception

from Meagher and Mitchel for having escaped without withdrawing his

ticket-of-leave, an ironic turn of events considering that Meagher may

very well have had a head start on his way to freedom in New York by the

time his withdrawal notice reached the governor. They, Meagher, and

Mitchel, were still acting in accordance with a peculiar British custom

that benefited the jailer to the detriment of the victim. However,

Donohoe being a working man was not forsworn to British gentlemanly

customs, certainly not the timely issuance of a notice to his jailers

that he was about to take his leave.

Patrick Donohoe was born into subjugation as were 8 million of his

countrymen and women. For almost all of his life he was subjected to

the laws of imperialism and the wiles of its

beneficiaries and enforcers in

Ireland. Although born on Irish soil he was denied his birthright to be

an Irish citizen by a usurper whose greed and cruelty had no bounds. As

an adult he aspired to be free and when the opportunity presented

itself, engaged in the struggle. The freedom he was denied in his

homeland he found in America. Unfortunately, it was short lived for he

passed away within a year of landing on America's shores. He died

suddenly on January 22, 1854, in New York before his wife and daughter

arrived to join him. He is buried in

Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY

Contributed by

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

CEMETERY

Name:

Greenwood

Cemetery

ADDRESS:

500 25th Street, Brooklyn, NY 11215-1755

SECTION

116, LOT 4173, GRAVE 261

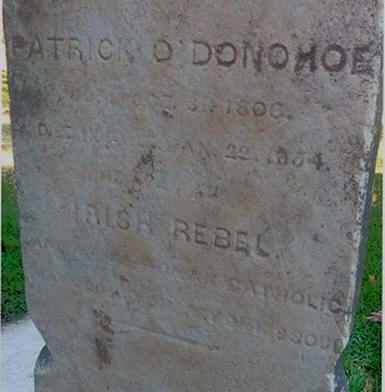

HEADSTONE

Photo Source ---

Patrick

O'Donoghue (died 1854) (igp-web.com)

Carlow County - Ireland Genealogical Projects (IGP TM)

|