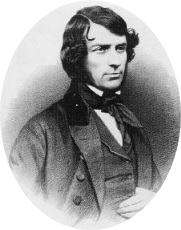

John Mitchel

(1815 - 1875)

Young Irelander, A Felon

of our Land, Author, Publisher, Supporter of the Confederacy

John

Mitchel was born on November 3, 1815 at the manse, Camnish,

near Dungiven, Co. Derry to the Rev. John Mitchel, a

Presbyterian Minister, and Mary (Haslett). In 1823 the

family settled in Dromalane House in Newry, when his father

became minister of Newry Presbyterian Church.

John

Mitchel was born on November 3, 1815 at the manse, Camnish,

near Dungiven, Co. Derry to the Rev. John Mitchel, a

Presbyterian Minister, and Mary (Haslett). In 1823 the

family settled in Dromalane House in Newry, when his father

became minister of Newry Presbyterian Church.

Mitchel received his early education at Dr.

Henderson's Classical School

in Newry

where he met his lifelong friend John Martin.

After completing his schooling in Newry he attended

Trinity College,

Dublin from whence he graduated with a law degree in 1834.

In 1837, he married seventeen

year old

Jane

(Jenny) Verner of Newry, by whom he had three sons and

two daughters.

After

completing his apprenticeship in 1840

he

practiced as an attorney in Banbridge where he met

the charismatic and influential nationalist

Thomas Davis the chief organizer the Young Ireland

movement, who at the time was assistant editor of the

nationalist weekly newspaper, The Nation, owned and

edited by Charles Gavin Duffy.

Upon the death of Thomas

Davis in the Autumn of 1845, Mitchel gave up his

practice in Banbridge and moved to Dublin where he assumed

Davis's role as assistant editor of the Nation.

Meanwhile he had joined the Daniel O'Connell Repeal

Association whose aim was to peacefully dissolve the union

with England. Disillusioned with the lack of progress he

joined the emerging Young Ireland movement, whose militancy

and advocacy of physical force were leading to a collision

between the older and younger leaders.

In July 1846, Mitchel, together

with

Thomas Francis Meagher,

William Smith O’Brien, Charles Gavin Duffy and others,

formally separated from O'Connell's Repeal Association, and

established the Irish Confederation. Mitchel assumed a

prominent role in the Confederation, openly advocating the

complete separation from England, a belief he fervently

advocated for the rest of his life. He firmly believed

that England would never grant Ireland any degree of freedom

willingly and concluded that physical force was the only

option if freedom was to be achieved.

In December 1847 Mitchel

resigned from the Nation

which he considered to be too moderate and in

February of 1848 parted company with the Confederation

in a dispute over the issue of resistance to the collection

of rates. Also in February of 1848 he published the

first issue of a weekly newspaper the United Irishman

whose motto for the paper was the words of Wolf Tone,

"Our independence must be had at all

hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they

must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that

numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of

no property." In the first issue he called for a

"holy war to sweep this island clear of the English name and

nation," and referred to the Lord-Lieutenant as "Her

Majesty's Executioner General and General Butcher of

Ireland".

In May 1848 Mitchel was

arrested under the new Treason Felony Act, convicted and

sentenced to transportation for fourteen years. After sentencing he was sent from Dublin

on board HMS 'Scourge' to Spike Island in Cork harbor where

he was incarcerated for three days. From there he was

transported to Van Dieman's Land, (now Tasmania) which he reached after spells

in the hulks (skeleton ships) in Bermuda and the Cape of Good Hope. Upon his

arrival in Van Dieman's Land he was granted a ticket-of-leave on parole and

allowed to live amongst his fellow United Irishmen,

including his old friend John Martin, Thomas Francis Meagher, Thomas

Bellew MacManus, and Kevin Izod O'Doherty, all of whom had been

arrested and sentenced, as was he, to transportation. His

wife Jenny and children joined him in 1851.

In June of 1853, Mitchel's

friend, Patrick J. Smyth, traveled from New York,

posing as correspondent of the New York Tribune,

to facilitate his escape. After surrendered his parole

and ticket-of-leave at Bothwell police station, Mitchel

made his way to New York via Hobart, Sydney,

Batavia and San Francisco. Upon arrival in New

York in November of 1853 he received a hero's welcome

from his fellow-countrymen.

After settling in New York

he edited James Clarence Mangan and Thomas Osborne

Davis collections of poetry. Together with

Thomas Francis Meagher he established the Irish

nationalist newspaper

The Citizen in which he serialized his Jail Journal,

a detailed account of his time in English prisons. The

Jail Journal was published in 1854 as 'Five Years in

British Prisons'. He also used The Citizen to

expose and condemn British oppression in Ireland and,

surprisingly, to defend the institution of slavery; arguing

that slaves in the southern states were better cared for and

fed than Irish cottiers (peasant farmers) or industrial

workers in English cities. In 1861 Mitchel wrote The Last

Conquest of Ireland in which he accused England

of "deliberate murder" for their actions during the 1845

Irish famine. An excerpt from the book reads as follows;

A

million and a half of men, women and children, were

carefully, prudently, and peacefully slain by the English

government. They died of hunger in the midst of abundance,

which their own hands created; and it is quite immaterial to

distinguish those who perish in the agonies of famine itself

from those who died of typhus fever, which in Ireland is

always caused by famine.

Further,

I have called it an artificial famine: that is to say, it

was a famine which desolated a rich and fertile island, that

produced every year abundance and superabundance to sustain

all her people and many more. The English, indeed, call that

famine a ‘dispensation of Providence;’ and ascribe it

entirely to the blight of the potatoes. But potatoes failed

in like manner all over Europe; yet there was no famine save

in Ireland. The British account of the matter, then, is

first, a fraud - second, a blasphemy. The Almighty, indeed,

sent the potato blight, but the English created the

famine....

The

subjection of Ireland is now probably assured until some

external shock shall break up that monstrous commercial

firm, the British Empire; which, indeed, is a bankrupt firm,

and trading on false credit, and embezzling the goods of

others, or robbing on the highway, from Pole to Pole, but

its doors are not yet shut; its cup of abomination is not

yet running over. If any American has read this narrative,

however, he will never wonder hereafter when he hears an

Irishman in America fervently curse the British Empire. So

long as this hatred and horror shall last - so long as our

island refuses to become, like Scotland, a contented

province of her enemy, Ireland is not finally subdued. The

passionate aspiration for Irish nationhood will outlive the

British empire.

As was typical of Mitchel he

could not reconcile his views with those of Meagher and as a

consequence the Citizen went out of business. After

that Mitchel spent some time in Washington DC working as a

reporter before relocating to Tennessee where he edited

The Southern Citizen.. When the American Civil War broke

out he moved to Richmond to edit The Enquirer,

the semi-official organ of Jefferson Davis, President of the

Confederacy. The war cost him dearly as two of his sons were

killed fighting in the Confederate army, John at Fort Sumter

and Willie at Gettysburg. His third son James lost an arm

in one of the Seven Days battles

around Richmond.

After the war ended Mitchel

moved back to New York to edit the New York Daily News.

His continued advocacy of the southern cause earned him

five months of confinement in Fortress Monroe in Virginia.

He was released after the Fenian organization interceded on

his behalf. After a year in Paris as financial

agent for the Fenians he returned to New York where in 1867

he founded the Irish Citizen.

By 1874 Mitchel had allied

himself with Clan na Gael. Flanked by the Clan leadership he

gave a speech at the Cooper Institute in New York describing

his recent trip to Ireland and denouncing constitutional

nationalism. He contributed his speaking fee to the

fund set up to rescue Fenian prisoners in Australia.

During his trip to Ireland in

1874 he ran for parliament from Tipperary and won a

lopsided victory against a conservative candidate. Although

he won he had no intention of taking his seat in as he

considered the Parliament an illegitimate body. In February

of 1875 the British Parliament declared him ineligible

to hold the seat as an undischarged felon. He was

subsequently re-elected unopposed in 1875.

John Mitchel died in Dromalane

House in Newry on 20 March 1875 nine days after his

re-election.

Mitchel's most important works

were: Life of Aodh O'Neill, Jail Journal,

Last Conquest of Ireland an edition of

Mangan's Poems, History of Ireland from the Treaty of

Limerick, and Reply to the Falsification of History

by J. A. Froude.

Click

here

for photos

relating to John Mitchel's incarceration on Spike

Island

Contributed by;

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

cemetery

Name:

Little Unitarian Graveyard

ADDRESS: High

Street, Newry, Co. Down, Ireland

HEADSTONE