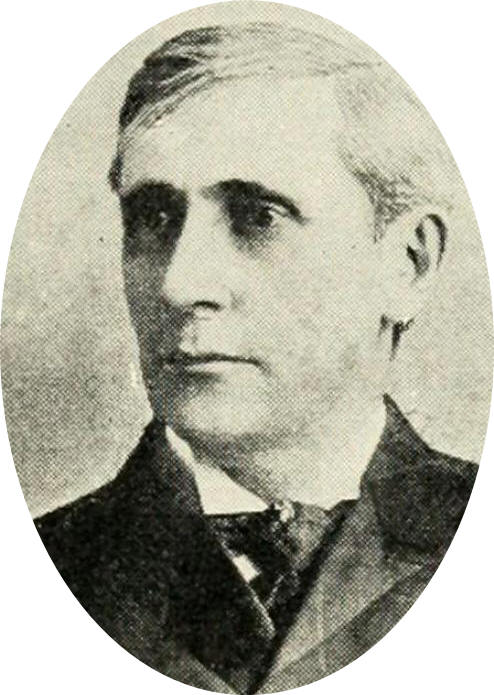

Michael Kerwin (1837 - 1912)

American Civil War Colonel, Fenian, Publisher, Republican Party Operative and NY City Police Commissioner

He put his life on the line for America, his adopted homeland, during the Civil War and afterwards proffered the same ultimate sacrifice for Ireland. A political animal by nature, he was as much as any other political operative responsible for the election of Benjamin Harrison as the 23rd President of the United States.

Childhood Years in Ireland

Michael Kerwin was born in Co. Wexford on August

15, 1837, the first of six children born to John

Kerwin and wife Catherine. Four of the children

were born in Ireland and two in the United

States.

Michael Kerwin was born in Co. Wexford on August

15, 1837, the first of six children born to John

Kerwin and wife Catherine. Four of the children

were born in Ireland and two in the United

States.

Michael came into the world at the onset of the Victorian Era in pre-famine Ireland, a period of abject poverty and borderline starvation. A third of the population depended on the potato for sustenance, an unpredictable situation that left them in a constant state of hunger in the early months of each year when the potato supply dwindled, rotted or sprouted and shriveled in the pits. Starvation was not the only malady that beset the poor. Adequate clothing was beyond their means, leaving them cold, malnourished and victims to the ever-present and ubiquitous diseases that bedeviled their lives.

The wretched souls who had reached the end of their rope and were unable to fend for themselves or their families became victims of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 that forced them into workhouses in order to survive. Within the workhouse, families were split up and assigned to separate quarters set aside for men, women and children. They were required to work depressing jobs, follow strict rules, and wear distinguishing workhouse clothing in exchange for shelter and a meager diet of bread and broth. For the keepers of the realm the choice was a simple one: bearing the cost associated with maintaining the workhouses or picking bloated bodies off the streets.

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 that repealed the Test Act of 1672 and the Disenfranchising Act of 1728, collectively known as the Penal Laws, provided a degree of relief for the native Irish who were predominately Roman Catholic. Although the Act was touted as "Catholic Emancipation" it came with impositions that rendered it lacking. The Act disenfranchised small landholders by changing the economic qualifications for voting from any man renting or owning land worth less than forty shillings to a higher threshold of ten pounds. It also placed onerous restrictions on the use of ecclesiastical titles by the Catholic hierarchy to ensure that the Anglican Church would reign supreme, a unifying force for colonial conformists.

As the title of the Act implied, the enactment of the Roman Catholic Relief Act by the British Parliament was not motivated by normal considerations such as homogeneity, social mores, prevailing attitudes or natural equality, but rather to forestall a potential uprising by the restive well-to-do Roman Catholics as manifested by the election of Daniel O'Connell, a Roman Catholic, to the British Parliament in 1828 in violation of the Test Act. In addition to the restive well-to-do Catholics, the activities and tactics of the Ribbonmen and Whiteboys, anti-Act of Union and agrarian-based organizations, were other compelling reasons to diffuse tensions and, hopefully, bring the well-to-do Catholics over to the side of the British-backed ruling elite.

One of the most meaningful outcomes of the Roman Catholic Relief Act was the establishment of the National School System in 1831 that ended the dependence on proscribed hedge schools under the Penal Laws as the only way to educate Catholic children. The few years that Michael attended one before departing for America probably amounted to his only positive experience of Ireland.

During Michael's ten childhood years in Ireland, the country was heading inexorably into one of the most devastating chapters in its long history---the Great Hunger years of 1845 through 1851. When the potato blight that precipitated the Great Hunger struck in 1845, Ireland became a death trap for the tillers of the soil who depended on the potato for sustenance, and for the urban dwellers who became victims of the nascent industrial revolution wherein British government policies favored England-based industries, leaving Ireland behind, dependent on a bespoke-based economy that was fast disappearing.

In America

The Kerwin family joined the exodus of 250,000 people leaving Ireland in 1847, the worst of the Great Hunger years. They were amongst the approximately starvation refugees that settled in Philadelphia that year. At that time Philadelphia was experiencing a rapid industrial expansion spearheaded by textile and iron and steel factories. The building of canals along the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers, the expansion of the railroad system and the naval shipyard offered many opportunities for both skilled and unskilled workers. For those immigrants with an entrepreneurial bent, opportunities abounded in myriad areas catering to the needs of newly arrived immigrants.

Apart from Michael, little is known of the Kerwin family in Ireland or in the United States. What they did for a living on either side of the Atlantic is unknown. One could surmise that they managed to eke out a decent living based on the fact that Michael was educated at a private academy in the city of Philadelphia, according to numerous accounts including Joseph Denieffe's A Personal Narrative of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, published in 1904.

After finishing his formal education Kerwin took up an apprenticeship as a lithographic printer.

In the late 1850s Kerwin joined one of the volunteer militia groups in Philadelphia where he received rudimentary military training. Militias were state-regulated groups of armed citizens that could be mobilized quickly by state authorities to help in natural disasters or to quell local riots and by the federal government to suppress insurrections or defend against an invader. A case in point was in 1844 when state authorities mobilized the militia to quell the Philadelphia Nativist Riots that took place in May and July of 1844 in Philadelphia and in the adjacent districts of Kensington and Southwark. The riots were instigated by armed nativists mobs incensed by the growing populations of Irish Catholic and other immigrant groups. To stop the killing and burning the authorities mobilized the militia who, during a period of days, killed or wounded dozens of rioters before putting an end to their rampage. At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, Lincoln depended on state-sponsored militias to supply the manpower need to suppress the rebellion by the southern slave states.

American Civil War

After Lincoln's call to arms on April 15, 1861, the day after the surrender of Fort Sumter, Kerwin was amongst the first to answer the call. He was mustered into service for three months on May 1, 1861 as 1st Sergeant in Company H, 24th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. In early June, the 24th Pennsylvania, attached to the 5th Brigade, 2nd Division, Patterson's Army, moved southwest to Chambersburg and in mid-June crossed into Maryland en route to West Virginia. Before the Army crossed the Potomac into West Virginia, Kerwin volunteered to go ahead, in disguise, to ascertain the strength and dispositions of rebel forces. During his foray into enemy territory he passed through their camps and defensive positions, making mental notes before returning to his post. With the intelligence gleamed from his report, the Army crossed the Potomac and engaged Confederate forces on July 2 at the Battle of Falling Waters. After a short engagement, the vastly outnumbered Confederate forces retreated, leaving Martinsburg to the Union Army. Shortly afterwards the 24th Pennsylvania moved on to Harpers Ferry and from there returned to Philadelphia where on August 10, 1861, Kerwin and the 24th Pennsylvania were mustered out of service.

Shortly after completing his service with the 24th Pennsylvania Regiment, Kerwin enlisted in the 116th Pennsylvania Volunteers, a squadron of cavalry under the command of Captain James A. Galligher and dubbed the "Irish Dragoons". The original intent was for the squadron to be attached to the New York--based "Irish Brigade" under the command of Thomas Francis Meagher. However, before that happened, President Lincoln issued manpower quotas to Pennsylvania and other states, thus forcing Pennsylvania to stop the transfer in order to help fill their own quota. After that development, the regiment was renamed the 117th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment, aka the 13th Regiment, Pennsylvania Cavalry. Before the 13th was deployed, Kerwin was commissioned Captain of Company B.

In April of 1862, the 13th Regiment was ordered to Baltimore, Maryland where it was attached to the 8th Corps, Middle Department guarding the Baltimore and the Ohio Railroad lines between Baltimore, Harpers Ferry, and Winchester in West Virginia through September of 1862, and afterwards scouting in Loudoun and Jefferson counties in Virginia until February 1863.

In October of 1862 Kerwin was commissioned Major, the third ranking officer in the regimental command structure.

In February of 1863, the 13th Regiment was assigned to Milroy's command at Winchester. From February through July of 1863 it was engaged in reconnaissance in northern Virginia and in the Shenandoah Valley in West Virginia. Before the disastrous Battle of Winchester in mid-June of 1863, it was engaged in reconnaissance and, after the battle, protected the rear of the routed Union Army on its retreat to Harpers Ferry.

In July of 1863, the 13th Regiment joined the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac under the command of General Meade who was in pursuit of General Lee's retreating Army of North Virginia after its defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg. The Cavalry Corps was under the command of General Sheridan. Moving south through Virginia the 13th Regiment took part in the Battle of Culpeper Court House in September that resulted in a Union victory. In October during the Mine Run campaign it took heavy losses while deployed as a picket force attempting to hold off a large enemy advance at White Sulphur Springs. Severely outnumbered, the 13th held its ground for six hours, resulting in heavy losses. After that it was assigned to duty along the Orange & Alexandria railroad near Bristoe Station during the winter of 1863-64.

In early May of 1864, the 13th was transferred to the 9th Corps and tasked with covering the rear of the corps during its march to the Wilderness. It took part in the ensuing battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and North Anna from May 8th through the 24th. Shortly after the 13th returned to the 2nd Brigade in late May of 1864, Kerwin was promoted to Colonel. During the remainder of 1864, the 13th was engaged in numerous raids, skirmishes and reconnaissance operations in support of the Army of the Potomac on its zigzag advance to Richmond. On several occasions from August of 1864 through February of 1865, Kerwin was called on to take acting command of the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division of the Cavalry Corps.

In February of 1865 during the siege of Petersburg, Kerwin was selected by General Grant to proceed by transport to Wilmington, North Carolina and from there proceed inland to meet up with General Sherman's Army on its march from Georgia through the Carolinas. After rendezvousing with Sherman’s troops at Fayetteville, the 13th was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Kilpatrick's Cavalry Corps, Military Division Mississippi, where Kerwin was given command of the brigade. From March through May of 1864, the Cavalry Corps advanced to Goldsboro and Raleigh where Sherman accepted the surrender of Johnston's 89,000-man Army on April 26, the largest surrender of the American Civil War. From May through July of 1865, the 13th was stationed at Fayetteville in the service of the Dept. of North Carolina, responsible for maintaining order in six surrounding counties.

The 13th Regiment was mustered out of service on July 14 and discharged in Philadelphia on July 27, 1865.

Back in Ireland

When James Stephens, cofounder and Head Center of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), returned to Ireland in early 1865 after an extended fact-finding trip to the United States, he informed his subordinates that 1865 was the year for action, the year for the Rising that they were all preparing for. Having decided to proceed, seasoned officers of the American Civil War, who were also members of the Fenian Brotherhood in the United States, were alerted to be ready to depart for Ireland on short notice to lead the IRB recruits during the Rising. Captain Thomas J. Kelly, an emissary of the Fenian Brotherhood, was one of the first to arrive in Ireland to assess the prospects for a Rising, and to advise on military matters. After receiving Kelly's favorable report, as many as 300 officers and other seasoned veterans were sent to Ireland, arriving there at different times via different routes. Kerwin was amongst the first contingent to arrive during the latter months of 1865.

As best as can be determined, Kerwin had joined the Fenian Brotherhood in 1862. Philadelphia, with its large population of Irish immigrants, was one of the prime centers for Fenian recruitment headed up by James Gibbons, the owner of a printing business. Kerwin may have been one of Gibbons's recruits. It's also possible that Kerwin joined the Fenians after enlisting in the Army, a recruitment honeypot for the Fenian Brotherhood.

Shortly after his arrival in Ireland, Kerwin was co-opted onto the IRB Military Council headed by Stephens. Other members of the Council included Colonel William Halpin, Colonel Denis Burke, Captain Thomas J. Kelly and Captain Doherty. Kerwin was also designated Judge Advocate, responsible for advising on the disposition of criminal matters such as court-martials, etc. Having decided on a plan of action, the Military Council awaited the go-ahead from Stephens.

In October of 1865 a split occurred within the Fenian Brotherhood in the United States between factions led by John O'Mahony and William R. Roberts, who differed on how to proceed: take the fight back to Ireland or attack British North America (Canada). Either out of an abundance of caution or a case of cold feet, Stephens used that as a reason for postponing the Rising. Thus, the best chance for a successful outcome was squandered by Stephens, a civilian with no military experience, overriding the judgment of five commissioned military officers who each had served four years in one of the most critical, deadly and high-stakes civil wars in history. Kerwin pleaded to proceed with the Rising, offering to share responsibility with his fellow officers for ordering it---to no avail.

In the meantime, the British government had suspended habeas corpus and were in the process of rounding up known Fenians with the help of informers including Pierce Nagle. The initial arrests in September of 1865 including Thomas Clarke Luby, John O'Leary and Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa. Stephens and some of the other top leaders were arrested in November. By February of 1866, all but two of the American officers on the Military Council were arrested. Kelly and Halpin had managed to escape the dragnet.

Kerwin spent the following six months in Mountjoy jail, refusing to sign a document stating that he would return to the United States and never return to Ireland. After six months he signed the document, realizing that a Rising was not in the offing. His fare back to the United States was paid for by Delia Parnell, the mother of Anna and Fanny Parnell.

Home in the United States

After returning to Philadelphia Kerwin settled down, married and fathered a daughter. It is known that he worked at various jobs including coal merchant, railroad contractor and postal clerk during the years he lived in Philadelphia. His experiences in Ireland did not sour him on the transatlantic struggle for Irish freedom. Undaunted, he continued to work with the Senate Wing of the Fenian Brotherhood, preparing for another invasion of Canada. He was the Fenian Secretary of War in the lead-up to the abortive invasion of Canada that took place in May of 1870. The first invasion took place in 1866 during his deployment to Ireland in 1865-66.

One interesting aspect of the period was that the Fenian War Department was located in Sussex County in New Jersey on a farm owned by General Hugh J. Kilpatrick who commanded the Cavalry Corps of Sherman's Army. As detailed above, Kerwin was given command of the 3rd Brigade, Kilpatrick's Cavalry Corps at Fayetteville in 1865.

After the failed invasion, Kerwin relocated to New York, presumably after his wife filed for a divorce. For the duration of the 1870s he worked at the United States Custom House where federal customs duties were collected on imported goods coming into New York. A political animal at heart, Kerwin joined the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, where many of his Civil War contemporaries made common cause. Over time he worked his way up through the ranks, eventually becoming a Republican ward leader, at the level where patronage was political currency to advance oneself and reward supporters and friends.

In 1883, Kerwin and David P. Conyngham became proprietors and publishers of the New York Tablet newspaper. Conyngham, who was born in Tipperary, was a Civil War Union Army officer and the Irish Brigade historian. The newspaper was an effective propaganda organ for the cause of Irish freedom and for the promotion of Republican Party politics. In the 1888 Presidential Campaign between Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican Benjamin Harrison, Kerwin used the Tablet to woo Irish American voters away from the Democrats. He used the Democrats' perceived affinity for all things British --- pointing to a British-owned vessel flying the Union Jack dredging the New York harbor as a prime example. That tactic alone peeled enough Irish American voters away from Cleveland in New York State to put New York in Harrison's column and guarantee the electoral college delegates he needed to secure the Presidency.

After the election of Harrison, Kerwin benefited greatly from plump patronage appointments. Over the following decade, Kerwin was appointed to numerous positions including Pension Agent for New York, Chief of the Registry Division of the state post office, Collector of Internal Revenue in the state service and in July of 1894 New York City police commissioner.

Sometime after his close friend Denis F. Burke, Colonel of the 88th New York Volunteer Infantry, died in 1893, Kerwin married his widow.

Like every successful political operative, Kerwin had his detractors. Although a member of Clan na Gael, the leadership of the Clan opposed his appointments, especially his Police Commissioner appointment. They could not oppose him on merit, as a hero of the Civil War. Instead, they opposed him based on his support of the so-called "Men of Force"---those who did not fall in line behind John Devoy's initiative dubbed the "New Departure". The initiative was concocted in 1879 in concert with Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt. It involved so-called moderate Fenians and Home Rule parliamentarians agreeing to set aside their differences in favor of pursuing a modicum of relief for tenant farmers and Home Rule for Ireland through parliamentary methods laced with agrarian agitation. The initiative was Devoy's alone as Clan na Gael refused to sanction it.

The "Men of Force" included Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, Thomas J. Clarke, Luke Dillon and others who believed that England only gave in to force. Kerwin was accused by his detractors of raising funds for the Skirmishing Fund that financed John Holland's Fenian Ram submarine, the Dynamite Campaign (1881-85) and the Invincibles, an IRB assassination squad responsible for the Phoenix Park killings in 1882.

Michael Kerwin, Irishman extraordinaire, passed away on June 20, 1912 at his home in New York. He remains were originally interned in Woodlawn cemetery in the Bronx, New York, and later reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery

He was survived by his second wife and daughter from his first marriage.

Contributed by Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

cemetery AND grave location

Name: Arlington National Cemetery

ADDRESS: 1 Memorial Ave, Arlington, VA 22211

SECTION: 3 LOT: 2169

HEADSTONE