|

Edward FitzGerald (1763 - 1798)

Irish Revolutionary, 1798 Irish Rebellion Martyr, United Irish Army

Commander-in-Chief,

British Army Officer, American Revolutionary War Participant,

Honorary Iroquois Chieftain

What was remarkable about Edward FitzGerald, a scion of nobility,

was his transformation from a defender of absolutism to a martyr of

liberty. His journey from a life of opulence to a hideout in Thomas

Street in Dublin was adventurous, transformational and tragically

fateful—a unique journey for a unique man. His life will be

remembered for the days he shared with his countrymen and -women in

their struggle for liberty and for his profound and fearless embrace

of their revolution.

Family

and Early Years Family

and Early Years

Edward FitzGerald was one of seventeen children born to James

FitzGerald, viscount and 1st Duke of Leinster, and

Lady

Emilia Mary Lennox,

the daughter of Charles

Lennox, the 2nd Duke of Richmond,

on October 15, 1763,

at the Carton House near Maynooth in County Kildare.

The Fitzgerald’s owned two more residences in Dublin: Frascati House

in Blackrock and Leinster House on Kildare St. Leinster House now

serves as Ireland's

Parliament House.

Edward's father, James, was a member of the Protestant Ascendency in

Ireland and as such served as a Member of Parliament in the Irish

House of Commons from 1741 until the death of his father in 1744.

Afterwards, having inherited his father's title, James served on the

Irish Privy Council and went on to hold several high-level military

appointments in the British military establishment. His numerous

titles resided in the ranks of both the Peerage of Great Britain and

Ireland.

Edward's maternal grandfather, Charles Lennox, was a politician and

a cricket enthusiast who inherited his title from his father, a

ranking member of the peerage of Great Britain.

When Edward's father died in 1773, his mother, Emilia, married

William Ogilvie,

her children's tutor with whom she had three more children. To avoid

the condemnation of her hasty marriage to Ogilvie, Emilia and her

reconstituted family went to live in one of her family's homes in

Aubigny in France where they remained until 1779. The years spent

there were formative years for Edward and his siblings in that they

were removed from the restraints of the staid norms of the English

aristocracy and exposed to a more realistic way of life. Edward's

mother, a non-traditionalist by choice, was open-minded and attuned

to the philosophy of the

Age of Enlightenment

sweeping Europe at that time. She embraced the ideas of democracy,

equality and liberty espoused by

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

and other philosophers and critical thinkers whose ideas were

leading the world out of the dark ages. Committed as she was to a

more inclusive and humane world order, Emilia was determined that

her children's education embraced modernity and an expansive view of

the world and that their choices in life would embrace critical

thinking, curiosity and humanity. One very obvious benefit of the

time spent in France by the family was their command of the French

language.

Military Career and American Revolutionary War

In addition to the formal education lessons FitzGerald shared with

his siblings, Ogilvie spent extra time with Edward, preparing him

for the military career he aspired to. In support of that goal,

Ogilvie instructed him in the basic requirements for a successful

military career included military history, responsibility and

discipline, leadership and teamwork skills, weaponry and battlefield

tactics. The other less formal aspect of Edward's education was

obtained by exposure to the smoldering revolutionary fervor directed

at the absolutist monarchial

governing systems prevalent throughout Europe. Full

realization of that aspect would come later.

Shortly after returning to Ireland, FitzGerald enlisted

in the

Royal Sussex Light Infantry Militia headquartered in Lewes in

Sussex, England.

His maternal uncle, the Duke of Richmond, was the militia's colonel.

It's assumed that Edward completed his mandatory training in Lewes

and afterwards joined the main body of the militia on coastal duty

in the vicinity of Brighton. In possession of a purchased ensign

commission, Edward joined the 96th Regiment of Foot as a lieutenant

after it was raised in April of 1780. After a period of service with

the regiment in Ireland he transferred to the 19th of Foot destined

for the American colonies to fight the rebellious colonists (the

American Revolutionary War).

The 19th regiment departed from Cork with seven hundred and thirty

men and arrived at Charleston, South Carolina on June 3, 1781.

On debarking at Charleston, the 19th

was deployed to Berkeley County in the vicinity of Lake Moultrie as

the British army was in a slow retreat through South Carolina

towards Charleston after having been driven out of Georgia. On June

21, Lord Rawdon with an army of 2,000 that included the 19th

regiment marched towards the fortified village of Ninety-Six under

siege by

1,000 troops under the command of General Nathanael

Greene.

As Rawdon and his soldiers approached the

village, defended by

550

Loyalists, Greene lifted the siege and retreated towards Charlotte

in North Carolina. Some weeks later

on July 17, 1781, the 19th took part in the Battle of Quinby's

Bridge and Shubrick's Plantation. The next battle the 19th regiment

fought in was the Battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8. That

battle, which the British won, was the bloodiest battle of the South

Carolina campaign. Nonetheless, it did not stop the British retreat

to Charleston. After four hours of hand-to-hand fighting, FitzGerald

was wounded by a bayonet gash to his thigh and left for dead on the

field. He was rescued by a South Carolina slave named Tony Small who

took him to his hut, attended to his wound and nursed him back to

health. Afterwards, Edward made his way back to the British garrison

in Charleston.

FitzGerald did not forget Tony Small's act of humanity

that gave him a second chance at

life. To that end he bought Tony's freedom and employed him as his

servant for the rest of his life. Having developed a kinship with

Tony, Edward brought him along on his subsequent travels

throughout Europe, America and Canada. As best as can be

determined, Tony was cared for by the FitzGerald family after

Edward's death.

In June of 1782, the 19th regiment including FitzGerald was sent to

St. Lucia in the West Indies where he joined the staff of General

O'Hara. It was the same

General O'Hara

who, in October of 1781, represented the British at the surrender

ceremonies at Yorktown wherein he surrendered Cornwallis's sword to

Washington's second in command. FitzGerald, along with the 19th, was

sent back to Ireland in 1783.

Postwar Years

On his return to Ireland in 1783,

and on leave from the army,

FitzGerald took up residence at Frascati House.

He also took a family seat in the Irish Parliament

for Athy in County Kildare, arranged by his brother William, the 2nd

Duke of Leinster. At the time he became a Member of Parliament,

Henry Grattan

had secured legislative independence for the Irish Parliament. Prior

to that it was subordinate to the Westminster Parliament. Its only

responsibility was to levy taxes. On entering Parliament, Edward

joined the reform-minded Patriot Party

led by Grattan. Although his

involvement in parliamentary debates was limited, he nonetheless

supported the aims of the party which included Catholic emancipation

and self-government for Ireland, aka Home Rule.

In 1786, with

little to do in the Irish Parliament and tired of lazing around,

FitzGerald

entered the

Royal Military College in Woolwich

to complete a course in officers' training. After

completing the course, he spent time

traveling through Gibraltar, Spain and Portugal. Still

unsettled after his

Mediterranean

sojourn, he

rejoined the British army in 1788 as a major in the 54th Regiment of

Foot in Canada. He served with the regiment in a number of

locations including Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Halifax, Quebec, and

Montreal.

In April 1789 after a year or so of military service,

FitzGerald

took another leave from the army and embarked on a hiking trek with

Tony Small and a fellow officer that took them from Fredericton in

New Brunswick to Quebec, a distance of 225 miles as the crow flies.

What was remarkable about the trek was that it was guided by

compass, it established a shorter, more practicable route than the

existing one and it only took twenty-six days.

During his ongoing travels through Canada

FitzGerald

met

Joseph Brant,

a Mohawk Chief and an ally of Britain during the Revolutionary War,

who showed him a snuffbox he received on a visit to London from a

Charles Fox who happened to be Edward's first cousin. After that

introduction they

became firm friends and travelled together by canoe across the Great

Lakes to Detroit. By the time they arrived in Detroit they had

exchanged their life stories. While in Detroit Brant introduced

FitzGerald to David Hill, an Iroquois Chief who at the behest of

Brant inducted FitzGerald as an Iroquois Chieftain.

From Detroit, FitzGerald under the tutelage of Brant and Hill

continued his journey

down the Ohio Valley to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans,

arriving there in December of 1789. Along the way he met with and

interacted and spent time with other native American tribes, an

experience that reinforced his growing beliefs in the "brotherhood

of man" as practiced by native American tribes.

His interaction and dependence on the generosity of the Indigenous

and tribal people exposed him to an egalitarian way of life that

appeared more natural, where everyone had worth and standing within

their tribe.

FitzGerald's

epic journey and the lessons learned left him with the realization

that the vast majority of his own countrymen and women were

suffering victims of the hierarchy at whose top his own family

perched. In reflection, he considered that state of affairs to be

unnatural and depraved, wherein the vast majority were subjected to

deprivation to fuel the avarice of the chosen elite. It was a

watershed moment in Edward's metamorphosis from defender of

absolutism to martyr for freedom.

The Revolutionary Years

After arriving back in England,

FitzGerald's

uncle the Duke of Richmond offered him the command of an expedition

to Cadiz in Spain to make

preliminary preparations for war. With the offer came a promise of a

promotion to lieutenant-colonel. In the meantime, he became aware

that his brother, the 2nd Duke of Leinster, had returned him to the

Irish Parliament for Kildare County. Considering a seat in the Irish

Parliament more important than commanding an expedition to prepare

for war, Edward declined the Duke of Richmond's offer, a refusal

that stymied his army career and opened a breach with the English

side of his family.

From 1790 through 1798

FitzGerald

held his seat in the Irish Parliament, advocating for the

marginalized and oppressed. His first open act of defiance occurred

in 1792 when he refused to back a proclamation condemning a group of

armed men who marched through the streets of Dublin sporting Irish

Republican regalia. In his refusal he stated, "for I do think

that the Lord Lieutenant and the majority of this house are the

worst subjects the king has". After hours of cajoling by other

members of the house he refused to recant.

In September of 1792

FitzGerald

journeyed to France accompanied by

Thomas Paine

who was fleeing England to avoid arrest on charges of seditious

libel as the author of the

Rights of Man,

which

severely rebuked monarchies and traditional social institutions.

FitzGerald and Paine spent time together in Paris where they engaged

in long discussions on many topics, including the nascent French

Revolution and the successful American Revolution. Paine, for his

part, had earned a claim to the title Father of the American

Revolution for his inspirational pamphlets including

Common Sense,

which

galvanized the rebelling colonists to sever ties with the English

monarchy and replace it with a constitutional Republic.

At the height of the French Revolution in November of 1792,

FitzGerald was amongst a hundred Republican-minded guests from many

countries who attended a banquet in Paris to celebrate the French

army's victories over the Prussian and Austrian invading armies. The

guest of honor was Thomas Paine. Twenty Irishmen, including the

brothers

Henry and John Sheares,

were in attendance. Amongst the many toasts given was one to

FitzGerald and Sir Robert Smith who took the opportunity to formally

renounce their monarchial titles in deference to their newly held

Republican beliefs. In responding to the toast, FitzGerald demanded

that henceforth he was to be addressed as "citoyen Edouard

FitzGerald". Shortly afterwards he was discharged from the British

army.

That historic event is considered to be a factor in the formation of

the United Irishmen as many of those in attendance became members

and later took part in the Rebellion of 1798.

In December of 1792, after a whirlwind romance in Paris, Edward

married Pamela Sims, a revolutionary in her own right who supported

the French Revolution. Shortly after his marriage to Pamela he

returned to Dublin with Pamela and took up residence in Leinster

House. They had three children.

Back in Dublin in 1793, he openly embraced radical politics and

railed against the establishment and his fellow Members of

Parliament, expressing his belief

that the house was packed on one side by the corrupt henchmen of

British power and on the other by ineffectual, rhetorically florid

''patriots''. He consistently voted

against government bills, including the Gunpowder and Convention

Acts aimed at suppressing unregulated militias and the United

Irishmen. He cropped his hair, dressed in plain clothes and walked

the streets of Dublin instead of riding so as to be in concert with

his fellow citizens.

The Society of United Irishmen,

Betrayal and Death

In the meantime, other events taking shape in Ireland would have a

profound effect on FitzGerald's embrace of radical politics,

particularly his embrace of Republicanism. In October of 1791,

Theobald Wolfe Tone,

a Protestant Dublin barrister, was invited by

Samuel Neilson

and Henry Joy McCracken to a meeting to discuss the feasibility of

establishing an organization to pursue Catholic emancipation and

parliamentary reform.

The invite was based on an earlier pamphlet authored and published

by Tone titled “An

Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland”,

which laid out the case for Catholic emancipation.

Tone accepted the invite, and together with Thomas Russell, a fellow

Anglican, met with Neilson, McCracken and seven other Presbyterian

reformers in Belfast. Arising from that meeting, the

Society of United

Irishmen

was founded on

October 18, 1791.

Prior to that, Tone had worked for

John Keogh

and other leaders of the Catholic Committee as

paid secretary to the Committee.

His work on behalf of the Committee helped it secure a modicum of

relief when the British Parliament passed the

Catholic

Relief Act of 1791.

However, the benefits derived thereof were muted by the passing of

subsequent repressive acts that stymied the exercise of the rights

set forth in the Relief Act.

Three weeks later, on November 9, 1791, Tone together with

James

Napper Tandy

established a

branch of the Society

in Dublin.

Shortly thereafter, on January 1, 1792, a newspaper called the

Northern Star, edited by Samuel Neilson, was launched in

Belfast. The newspaper promoted the Society’s ideas by demanding “a

society of equality which would include people of all religious

persuasions—and of none”. As membership in the Society increased

at a rapid rate and branches popped up throughout the country, the

British government became alarmed and began to clamp down and arrest

its leaders.

In 1794, no longer free to operate

openly, the Society was reorganized into a

secret revolutionary organization

dedicated to the overthrow of the monarchy in Ireland and for it to

be replaced by a Republic along the lines of the American and French

Republics. By then

FitzGerald was living in a cottage in Kildare town where he had

started to visit local pubs, play Gaelic games,

learn Irish and use turf instead of coal—in

other words, live as the locals did.

In addition to his new lifestyle, he made known his desire for a

free and unfettered Irish Republic. His easy manner and natural

leadership qualities impressed local young men who shared his views

and were prepared to follow him into battle for the Irish Republic

he was advocating for.

By then he was fully committed to total separation from England in

line with the stated aims of the Society of United Irishmen.

Aware of the Society's plans, the Irish Parliament enacted the

Insurrection Act

in

February of 1796

to forestall an insurrection and to indemnify the British army and

the yeomanry from the consequences of the savagery they would be

allowed to pursue in quelling an insurrection.

It is not known exactly when

FitzGerald became a member of the

Society of United Irishmen as accounts vary from late 1795 to early

1796. Irrespective of when he joined, his family name, affable

demeanor, keen judgment and military background propelled him into

the ranks of the Society's leadership. In short order he became

Commander-in-Chief of the United Irish army.

In May of 1796, together with

Arthur O'Connor, FitzGerald

journeyed to Hamburg to meet with French General Hoche to seek

French military assistance for an insurrection in Ireland. At the

same time, and as part of the same mission, Wolfe Tone was in France

consulting with the French government.

On December 16, 1796, a French expeditionary force consisting of

forty-three vessels and 15,000 soldiers set sail from Brest under

the command of General Hoche. Wolfe Tone was aboard

the flagship Indomitable with General

Hoche. Arriving off the Kerry coast they were unable to land due to

gale-force winds. They waited for six days in Bantry Bay for the

winds to abate before returning to France.

Contemptuous of body politics and his fellow Members of Parliament

as biased and ineffective,

FitzGerald stepped aside in the

general election of 1797, explaining that he could not in good

conscience serve on a body so out of touch with the needs of the

people. By then he had reached the point of no return in his

rejection of his former life as an aristocratic elitist. He

commitment to the cause of liberty and the establishment of an Irish

Republic was sacrosanct Consequently, he was fully reconciled to his

fate, particularly if the looming insurrection failed. To that end,

and aware that his family could also be a target for reprisal, he

took steps to ensure the safety and well-being of his children by

placing them in the care of family members in England.

Through informers such as Leonard MacNally, Samuel Turner, Thomas

Reynolds, Francis Magan, and Richard

Newell, Dublin Castle was aware of

the Society's plans to effect an insurrection and of

FitzGerald's involvement. Regarding

Thomas Reynolds, it was FitzGerald

who had recruited him to the cause, and as a result of his

leadership skills Reynolds was made a colonel of the United Irish

forces in Kildare.

The arrest of Arthur O'Connor in 1797 for high treason left

FitzGerald without a strong ally in

planning and preparing for the insurrection. Nonetheless, by

February of 1798 he had drawn up detailed lists of the number of

recruits available and ready for battle in Munster, Ulster and

Dublin. Naive to the world of spies and traitors, FitzGerald

gave a copy of the lists to the aforementioned Reynolds who

immediately passed it on to his handlers in Dublin Castle. Some

weeks later Reynolds, who had found out where the United Irishmen's

Leinster Provincial Committee would be meeting, passed the

information on to his handlers. In the ensuing British raid, a

number of the Committee's leading members were arrested.

FitzGerald was not amongst them.

Subsequently an arrest warrant was issued for his capture and raids

were carried out at the Frascati and Leinster House residences.

Edward narrowly escaped capture at Leinster House after being

alerted by Tony Small of the approaching raiding party.

After that narrow escape, a public

proclamation was issued offering a reward of £1,000 for information

leading to his arrest. By then he was the most sought-after man in

Ireland. Despite the danger he continued to move around Dublin

using many disguises, even at times dressed as a woman. Some of his

trips outside Dublin were to reconnoiter advance routes into

Dublin from Kildare for the United Irish forces in taking control of

the city.

On March 30, 1798, the government declared martial law and

instructed

the army and yeomanry to use whatever means necessary to crush the

United Irishmen.

As part of that government directive General Lake, who had directed

a campaign of terror in Ulster after the failed French landing in

1796, had his mandate of terror extended to the whole country. After

FitzGerald

received word from France that another French armada would not

arrive until August it was decided that they could not wait and

brought the launch date forward to the 23rd of May.

On May 17, 1798, the informer Francis Magan found out where

FitzGerald

was hiding and passed the information on to his handlers in Dublin

Castle. A few days later on March 19, Edward's hiding place on

Thomas Street in Dublin was raided by yeomanry agents of the British

army. In the ensuing struggle, FitzGerald killed one of the agents

and wounded another with his dagger before being shot twice in the

shoulder. He was taken to Dublin Castle where two pistol shots were

removed, and the wound dressed.

After that he was removed to Newgate Prison.

After languishing for weeks in Newgate Prison his wound became

infected with septicemia. For lack of care the infection

progressed to sepsis shock or some other fatal condition. At 2 am

on the morning of June 4, Armstrong Garnett, a young Dublin surgeon,

recorded in his diary the following entry, ``After a violent

struggle that commenced soon after twelve o'clock, this ill-fated

young man has just drawn his last breath. - 4 June 1798.''

Edward

FitzGerald

was 35 when he died.

After his death,

FitzGerald's

sister,

Lucy Anne,

issued a statement on his behalf:

“Irishmen, Countrymen, it is Edward FitzGerald’s sister who

addresses you: it is a woman, but that woman is his sister: she

would therefore die for you as he did. I don’t mean to remind you of

what he did for you. ‘Twas no more than his duty.

“Without ambition he resigned

every blessing this world could afford to be of use to you, to his

Countrymen whom he loved better than himself, but in this he did no

more than his duty; he was a Paddy and no more; he desired no other

title than this.”

FitzGerald

had previously said that he was a "Paddy" and no more, and that he

"desired no other title".

Contributed by Tomás Ó

Coısdealbha

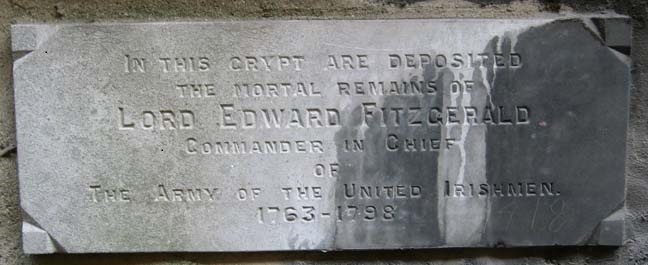

BURIAL

PLACE

Name:

Saint

Werburgh's Church

ADDRESS: 7-8

Castle St., Dublin, Ireland

CRYPT

|