|

Frances Isabelle Parnell

(1848-1882

Irish Patriot, Poet,

Writer, Human Rights Activist, Founder of the Ladies Land League in America

"That moral energy which inspires men with the ability and the desire to

oppose themselves to injustice, to protest against the abuse of power,

even when this injustice and this abuse do not directly affect them is

the virtue which is the guaranty of order, security and independence".

Montalembert, 'Monks in the West'

(quoted by Fanny Parnell in 'The Hovels of Ireland' to explain why her

land-owning family were Irish nationalists)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Early Years

Fanny Isabelle

Parnell was born in Avondale, Co. Wicklow

on May 13, 1852,

the eight of

the eleven children born to John Henry Parnell

and his American-born wife, Delia Tudor Stewart, the

daughter of

Rear Admiral Charles Stewart, US Navy.

Fanny's parents came

from historically high profile families with

politically divergent backgrounds rooted in colonial bondage

and wars of national liberation. Their

respective Anglo-Irish and Anglo-American

backgrounds and underpinning loyalties fostered

within their respective domains a century of

bitterness and mistrust despite their

common Anglo-Saxon Protestant heritage. Outside

of the family unit, each of Anna's parents lived

their own high profile life according to the

value system inherited from their forebears.

Fanny's paternal

family lineage can be traced back to a Thomas

Parnell in Chersire, England in the early

years 17th century. The first Parnell to settled

in Ireland was a grandson of Thomas Parnell who

purchased land in Ireland circa 1660. Members

of successive generations became active in

politics, four of whom served as MP's in the Irish

Parliament. Two of them had distinguished

careers including Sir William Parnell MP

who vigorously opposed the Act of Union and advocated for Catholic

rights. His son Henry Parnell who served in both

the Irish and Westminster parliaments also opposed

the Union before and after it became a

lamentable actuality in 1801. As best as can be

determined, all of the landed Parnell's were

reasonable landlords who valued and treated their tenants

and farm workers with respect.

Fanny's grandfather on the maternal side of

the family, Rear Admiral Charles Stewart was commissioned a

lieutenant in the US Navy in March 1798. His first assignment as a fourth

lieutenant was aboard the frigate United States under the command

of

John

Barry. During his long and distinguished carrier,

Stewart served in the Quasi-War with France, in both the Barbary and

Mediterranean wars and in the War of 1812 with Britain. He was promoted to rear-admiral in 1862.

Fanny's great grandfather, William Tudor, was the first Judge Advocate

General (JAC) of the US Army. He was appointed by George Washington in

July of 1775 at the age of 25. Williams father John, a wealthy

businessman, was born in England in 1708.

Delia Tudor Stewart, Fanny's mother, was

wary of the British establishment, a trait she

inherited from her distinguished ancestors. However

deep that feeling there is no doubt that it was exacerbated by

what she witnessed firsthand in Ireland, the dehumanization of the Irish

people by the same British colonial juggernaut that her ancestors

vanquished a century past. In hindsight it's evident that Delia's

convictions and sense of independence were passed on to Fanny and her

sisters. On the male side of the family the inclination was

weighted in favor of the pomp and perceived chivalry, the trappings of

the British Empire so closely linked to the Parnell's, albeit, not

always favorably.

As there is no information available regarding the children education

its assumed that they were coached by private tutors. Its obvious from

Fanny accomplishments during her short life that she was highly

intelligent having studied mathematics, chemistry, and astronomy and

mastered almost all the major European languages. She was also

accomplished in music and painting.

In 1859, following the death of her father, Fanny moved with her family

to Dalkey, Co Dublin and in 1860 moved from there to Dublin. Fanny took a great

interest in Irish politics and attended the trials of the Fenians. In

1864, under the pen name 'Aleria' she began publishing her poetry in the

Fenian Brotherhood's newspaper the Irish People founded in 1863 by John

O'Leary and others. When the newspaper was suppressed by the British in

1865 she contributed articles and poems to the Nation and

United Irishman newspapers.

In 1865 she moved with her mother to Paris and then in 1874 to

Bordentown in New Jersey, While in Paris she cared for wounded soldiers

in the four month long Siege of Paris (1870-1871) during the

Franco-Prussian War.

In 1880 Fanny founded the Ladies' Land League in America to raise money

for the Land League in Ireland. A pamphlet, The Hovels of Ireland

(1880), and a collection of poems, Land League Songs (1882),

were widely published. Her best known poem

Hold the Harvest was

described by

Michael Davitt, leader of the Land League, as the

'Marseillaise' of the Irish peasant. Most of her work was published in

the Boston Pilot, the leading Irish newspaper of the 19th

century in America.

Little is known of the amount of work that Fanny and

Anna, her sister,

put into the running of the Land League Committee. It was Fanny, the

Patriot Poet, who appealed to Irish-American women to form an relief

fund to help the Land League in Ireland. Anne, the most radical of the

sisters, was responsible for all the funds collected. She acknowledged

every contribution and saw to it that the money went to the right

quarter. The $60,000 collected for the relief fund came from poor Irish

immigrants in cities around America. The money went a long way in

averted another famine in Ireland in 1879 and 1880.

Fanny and Anna's work in support of the tenant farmers in Ireland did

not go unchallenged in America. On June 2, 1882, Bishop Gilmour of

Cleveland, Ohio issued a Card to the ladies of the Land League

threatening their excommunication unless they renounced all relations

thereto. They refused to comply and told him to mind his own business.

In response the bishop issued his Card which was read in all diocesan

churches. Despite his best efforts the women of the Ladies Land League

held their meeting as scheduled and went on to declare,

"we have done

nothing wrong against the Church as Irishwomen, we have organized a

society to aid Ireland. If that be heresy, then we are heretics".

Following her return to Dublin in 1880, Anne founded the Irish branch of

the Ladies Land League, which became a formidable force. When Michael

Davitt, Charles Stewart Parnell and other Land League leaders were

imprisoned in 1881 the Ladies' Land League took over their work. Other

than an office in Dublin very little else was provided in the line of

help or instructions. Nonetheless, the women were not daunted by the

task at hand, proceeding to hold public meetings encouraging tenants

to withhold rent, resist evictions and boycott landlords. They raised

funds to support prisoners and their families and built wooden huts to

shelter evicted tenant families. By 1882 they had five hundred branches,

thousands of women members and considerable publicity. Their meetings

were frequently broken up by police. Thirteen of their members were

imprisoned not as political prisoners like the men but as common

criminals. Considered the first modern Irish female agitator, Anne

became estranged from her brother after he withdrew support for her

movement.

The Parnell women were indeed in the forefront of the Women’s Liberation

movement and were passionate advocates for human rights. Together with

the thousands of other women activists they showed how the women of

Ireland could be just as tough as men when the need arose.

Fanny Parnell died on July 20, 1882 at age 34 in Bordentown, New Jersey.

The original plan was to have her remains sent back to Ireland for

burial, however, her brother Charles opposed that plan stating,

"Wherever you die you should be buried."

Parnell's posture regarding Fanny's final resting place was not based on

some unique family norm or known cultural trait as he had made no such

plans for his own demise. When he died in England in October of 1891 his

remains were brought back to Ireland for burial. The reason he did not

want Fanny remains returned was to prevent one of the largest display of

reverence ever seen in Ireland for a beloved and honored patriot. Fanny

and her sister Anna did more for the suffering tenant farmers and the

tenement dwellers in Ireland than the egotistical and misogynistic

Charles and his Irish Parliamentary Party cohorts ever did for Ireland

or its people. Such a display would be embarrassing for Charles after

having made a deal with Gladstone to disband the Ladies Land League in

Ireland in exchange for his release from prison.

Once Charles made his wishes known, plans for her funeral proceeded.

After a long funeral procession by train to Boston, by way of

Philadelphia and New York, the casket bearing her remains was open for

family and friends to view at Tudor home on Beacon Hill. After the

viewing her coffin was placed in the Tudor family vault at Mount Auburn

Cemetery in Boston.

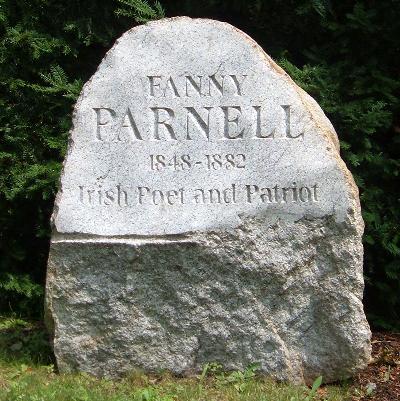

On April 11, 2001, the Parnell Society of Dublin placed a granite marker

at the grave site, honoring her role as a patriot and poet of Ireland.

Chick

here for additional Funeral details.

Contributed by

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

cemetery AND grave location

NAME: Mt. Auburn

Cemetery

ADDRESS: 580 Mt. Auburn Street,

Cambridge, MA 02138

HEADSTONE AND INSCRIPTION

|